[Originally posted 14 August 2016]

I've mentioned more than once that this entire work of fiction is based on a game, and I'm long overdue for explaining what I mean.

Before it was a web site, the Heroes Universe was a Role-Playing Game (hereafter referred to as RPG for short).

RPGs have been around for more than 40 years, with Dungeons & Dragons being the first and probably best known example. Obviously they are games, and they involve a group of people sitting round a table and moving pieces around, but other than that they're completely different from how "traditional" board games work. For a start, they take place mostly in the players' heads rather than on an actual board.

In an RPG, players don't compete against each other, they work as a team to solve some puzzle, problem, or conflict. One of the players creates the puzzles for the rest to solve. He is traditionally called the "Games Master" (GM). Some games use different terms, but I prefer GM so that's what I'll use here.

That's an RPG in a nutshell. But that's very superficial. To understand better, we have to look at how the GM creates the "puzzles" for the players.

First, I don't mean a simple puzzle like, "Rearrange these matchsticks to make a triangle". I mean a puzzle like, "You have been sent back in time to the year 1987 where you have to stop an extra-dimensional threat from destroying the universe." Ok, from now on let's say "plot" rather than "puzzle," because that's basically what I've just described. That sentence could be the plot of a novel.

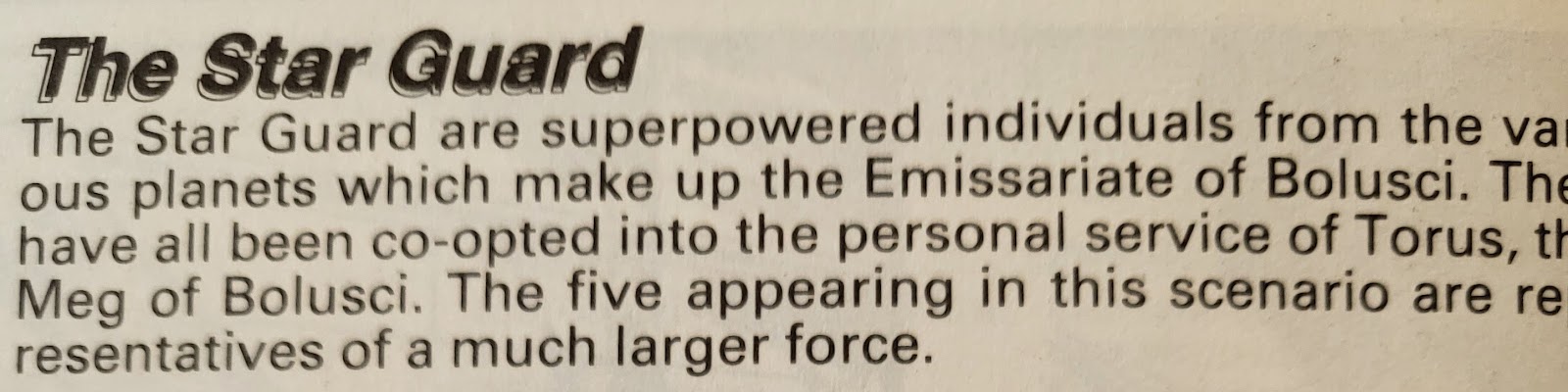

Once the GM has the plot, he needs to create a setting to put it in. So he creates a world -- he thinks up some background details about the 24th century, comes up with the idea of a super-powered police force, and so on. Next, he needs an antagonist for the plot -- let's say, a super-powerful robot from some place called "Dimension W", who is sending a signal to summon his invasion fleet. Finally, he needs to know how the puzzle can be solved -- let's say smashing the robot's communication machine is the answer, but let's make it difficult by protecting it with a force field, and furthermore having the army unwittingly helping the villain.

That's the GM's job finished. (Well, the easy part of it. He has more to do later.) All of this springs entirely out of the GM's head, of course. He's bought a rule book for the game, but that doesn't tell him what plot to use. He has to write his own plots. And he's the only player involved in the game so far; he's shut in his room on his own writing all this down ready for when the rest of the players come round on Saturday. (Being a GM is a good job for people who like writing stories. That's why I do it.)

Now the players come in. The GM describes the idea behind the game to them -- "You're police officers in the 24th century." That's literally all he needs to tell them. Well, he might need to elaborate on details, but at the moment the setting is all they need to know. He doesn't tell them the plot in advance, because the game happens when they uncover the plot for themselves.

As the GM is responsible for supplying the plot for this story, so the players are responsible for supplying the characters. The GM will ask each one of them to create a character that could fit into the story he wants to tell. Based on the background he's revealed so far, one player might say, "My character is a futuristic secret agent trained in espionage and unarmed combat", another might say, "I'm a genetically-engineered human, faster and tougher than ordinary men". Another might give the GM a complete headache by saying, "I'm a demon!" (Great, thanks, did you miss the part where I said I'm doing science fiction?)

The rule book the GM has bought will give rules that allow him and the players to define exactly what their characters can do -- how fast they are, how strong, how good at fighting or sneaking around -- but that's not the important part of the character. The important part is when the player says, "My character loves reading old comic books and always dreamed of being a super-hero, that's why he's in the super-police. Also, he makes bad puns." That is a character. That's what you need to know when you read a story: not how fast the character can run but why he's doing what he does.

Everything is ready. Then the actual play of the game starts, and the GM's actual hard work starts.

First, he describes where the characters are, why they are there, and what they can see. "Your team reports as ordered at the Institute for Temporal Studies, teleporting there [he has explained how his future world works, so they know about teleporting around the world] as a group. Two guards are at the door ... and Nightflyer's intuition is giving him bad vibes about them."

Then the players describe their actions: "I'll challenge the guards," "I'll punch one of them," and so on. That's why its called a role-playing game. Each player plays the role of a character within the game world. You try to act "in character" -- speak as you have decided the character will speak, pretend that you know only what the character should know, say that your character is doing things that make sense for the personality and motivations you have created for him. None of us are under any delusions that we are great improvisational actors, but in effect that is what we are doing.

The GM will determine the results of the players' actions (this is where the rule book often does come into play, as you might actually need to know how strong or fast the character is to decide if their actions succeed) and describe what happens next. Then the players (acting "in character") give their responses, and the story is driven forward.

While the players are acting the roles of their characters, the GM only (!) has to act the role of every other person in the universe. The two guards at the door? That's me. The villains inside? That's me. The chief of police? Scientist? Computer? All me. Everybody the players' characters might interact with in the world has to be created and acted out by the GM. Sometimes I've played multiple characters at the same time, arguing with myself while the players watch. Oh, and at the same time I'm making sure we use the rules properly, I'm trying to be fair about allowing their actions to succeed or not, I'm weighing up the implications and deciding what should happen next if they do/don't succeed, I'm remembering what plot secrets I have and haven't told the players yet, remembering everything the players have told me about their characters, and desperately hoping I will be able to think up an answer on the spot for when the players ask me something about the world that I haven't thought of in advance.

Because obviously, although the GM knows how he wants the story to go, he has no control over what the players might do at any given decision point. Perhaps they misunderstand a clue he gives them and go the "wrong" way. Perhaps they react in a way he didn't expect. Perhaps they ignore the villain completely and spend four hours arguing among themselves. (Yes, I have have had afternoons like that.) Literally anything can happen when the characters created by the players meet the plot created by the GM.

And that's what the GM loves. Because for four or five hours on a Saturday afternoon, he and the players are literally making up a new story, set in a world he has created. We call it a game, but the truth is, it's a collaborative work of fiction.

And that work of fiction, documented over the course of almost 30 years, is what you're reading on this web site.

I designed the world, but it's not my story. It's theirs. Ours.